American Suicide Culture

Self-euthanizing & suicide are NOT the same things

Another ending in a morning’s headline “Anthony Bourdain Suicide at age 61.”Most everyone knew who he was, the master chef and globetrotter hosting a program called Parts Unknown about the food and drink and people from far-flung corners of the world.

He hanged himself in a hotel room in Paris (France, not Texas).

Another ending of a life we imagined we knew something about, but that we then had to wonder, did we really know anything at all? And not just this American’s life, but his death.

Robin Williams, Kurt Cobain, Hemingway (many years ago, but the shotgun blast still roars in every writer’s ears), so many others: ingénues, movie stars, and rock icons, Jimi, Janice, J. Morrison. Were these all really “accidental’ O.D.s from such experienced heroin addicts?

People in many countries kill themselves for a wide range of apparent reasons, but in America, there seem to be more and more suicides for reasons invented after the act, more like half-assed efforts to explain/justify than believable and genuine explanations that make sense.

I expect to someday self-euthanize, although I’m far from sure that I’ll do this and very sure that it won’t be any time soon.

I am far more certain that I’ll never commit suicide, as in hanging myself or blowing my brains out or any of the other grand dramatic gestures and salutes to my special, final suffering and anguish, regardless of how real and painful those feelings are.

I can’t promise this, but I am as sure about it as I am about anything else in my life.

Hunter S. Thompson was not the only person to gather together his loved ones and inform them of his decision to leave his life. Jerzy Kosinski wrote Painted Bird one of the strongest most brilliant portrayals of a fight to survive ever written, yet when he felt and knew his mind was going from Alzheimer’s he quietly left the stage while he still had a choice in the matter.

I won’t end it all with any of what often appear to be self-absorbed and dramatic closures, meant to punish the world somehow for failing to let me feel like I still matter. But in truth, suicides of that variety are simply, another ending;

And they are an increasingly common kind of American ending.

I figure it like this: We hope to matter, expect to matter in our lives, while secretly we know, a secret even to ourselves, that in America if you’re no longer either producing or consuming (preferably BOTH) what the hell good are you? Why are you still here taking up space? Want some applicable proof? Here you go:

175K (and counting) dead from a virus that every other country in the world has managed to control to at least some degree and in every one of those countries a greater degree than in America. And this virus most aggressively kills the old and the weaker, the poor, and people of color in the most exposed and dangerous work situations.

If you think that the American acceptance and rationalizations for suicide and the death numbers of our present pandemic are unrelated — no offense, but you are not thinking clearly.

I don’t want to live forever, well, maybe I DO, but I won’t and can’t.

What I DO want, what I demand of myself, is to live today as if it is forever.

I intend to remember every day that every moment is as close to forever as any of us will ever get.

Let’s never let America convince us otherwise. Let’s live our lives by our right purpose and right understanding and keep walking past those open 12th-story windows.

In a Big Country

Come up Screaming, here and now.

In 1983, Scottish band Big Country released “In a Big Country,” which popularized quickly in the heavy air time given by MTV. Like all classic eighties songs, the piece has that distinct new wave sound, but Big Country uniquely used electric guitars to mimic bagpipes, adding to the song’s longevity. Anthemic and catchy, the song to this day has many nostalgic and new listeners, but perhaps empowering the song most are the meaningful words so often overlooked in the music’s beat and feel. For that message provides us real wisdom — if we listen and apply.

Father’s Day

My Father's father hung himself in our home when I was a toddler. My dad refused the medication that could have kept him alive, and in doing so, ended his life. Suicide or self-euthanizing? What's the difference? Both lead to death but perhaps the legacies are not the same.

I miss my dad. Not that whole dewy-eyed, sentimental, made-For-TV kind of miss him. Not Disney or sitcoms or the hero of the story whose kids all adore him (though none of them have any speaking parts so who can tell for sure?)

I don’t miss his constant wisdom (if there ever was any) or witty lessons (if he ever offered any) and I don’t miss our long walks/ talks/fishing trips (because we never had any) or throwing a ball or his wise sayings about life etc. etc. etc. blah blah blah, none of which, also, ever happened.

I don’t miss the feeling of being afraid of him or later, I don’t miss feeling glad or bad about disappointing him, which were major emotions for me with him and are permanent memories of our ‘Relationship,’ such as it was.

I don’t miss his corrections, sometimes sarcastic and caustic, sometimes just flat-out cruel.

Nor do I miss the very few times he angrily laid hands on me his face twisted into something, between exasperation and hateful rage — so, I miss him? Really? How? Why?

What I miss is what I imagine he and I might have been together if our roles, father and son hadn’t been so stupidly assigned and accepted — I miss how we might have been friends if we’d been just a couple guys, who met under different circumstances, like two strangers in a bar flirting with a couple pretty women, good looking blond sisters, and this stranger and I realizing, we needed to work together to pull off anything good before ‘Last call’. In other words, I miss my dad, not for whom he was but for who we might have been — I miss the guy he couldn’t be with me and I miss the guy I could never be with him. The best I can manage now is to confess that if all the rules about loving family weren’t real (and I think they aren’t) I’d still miss my old man, for reasons I don’t begin to understand — or need to.

In a Big Country Dreams Stay With You

I can’t speak for most of the world, but in the US and UK, this song held much fascination mainly because eighties youth interpreted “Big Country” as “opportunity.” Dream manifestation has a unique mystique in the western world for the young who see no limitation to their vision. Perhaps it is that way in Eastern countries, I don’t know for sure, but in the US, this boundless sense of dream actualization touches even those often excluded: the poor, the abused, the oppressed, etc. The dream manifestation’s magical thinking tailors many personal visions. The inner-city kid living in poverty might envision college or a job as a life-altering, affluence-bringing goal. The small-town kid might see the move to a big city or larger town as the vision quest. Everyone conjures dreams differently because in that big country, anything is possible.

My Father’s Hands

Family, which some of us actually manage to survive

The house where I grew up sometimes became my father’s hands — I remember him, angry, staring at me those hands with braided fingers wrapped around themselves, cold and hard.

His nails were smooth as spilt milk; his flesh an unripened pear. I remember sitting across from him, waiting while he waited for me, and this became proof-positive that there is no god I cared about pleasing because there is no god at all.

A Lover’s Voice Fires the Mountainside

The power of hope is amazing. So amazing that many often view dreams as spells capable of altering reality when invoked by faith in their actualization. Seeing hope in this way is easy, sometimes life-affirming, but often disappointing. Yet, hope engulfs us like a conflagration, searing us with purpose, and often provides the only driver to continue, but she is not blind faith or a guarantee of a fantasy.

She fires across the mountainside a choice.

Hey Hemingway, Chickenshit Check-Out

Why I have a right to these feelings

Hemingway was cleaning his shotgun when it accidentally went off and blew his brains out, said his wife.

He’d won the Nobel Prize and was wealthy and had been featured in lots of magazines because he was such a tough guy.

But, accidents happen and it’s nice to have a 4th and (as it so happened) final wife to clean up the mess.

When you’ve looked into the face … of a loved one who has just killed himself, within that hour and you’ve found the body, you can criticize suicide anytime you feel like doing so.

And if someone doesn’t like you doing that, that’s fine but keep in mind unless they’ve gone through the same horrors you have, they don’t know shit about it.

I’ve written about this before, written about it in nightmares and staring out the window through which I could first see him hanging there, and written about it without writing a word by the breaths I’m breathing thinking about him and remembering that day which no amount of writing will ever fix or repair of that moment of looking into his face.

Posting today, the 25 anniversary of my beloved stepson’s suicide.

Come up Screaming

In 1999, while attending a martial arts class, I asked a veteran fighter about falling during combat, and he laughed, “You just gotta come up fast, screaming, and swinging.” His phrasing invoked In a Big Country, which ironically described how the last nine years felt recovering from life’s mat after a crappy career, failed marriage, and many other knockouts. Constantly pulling myself up created much futility, hampered by so-called wisdom, especially religion, which I recently discarded. If you tell yourself long enough to “believe” or “faith without works is dead” and many other adages, you’ll either prove these statements false or endure endless disappointment convincing yourself. Standing in the martial arts studio, alone in my doubt, raised the question of why I did certain things like practicing martial arts?

Having taken martial arts years prior instilled a sense of comfort, knowing the practice benefited me in the past with community. Longing that benefit formed a seeming escape from the doldrums of working and coming home to no family and having few friends. Luckily, I met many people and removed myself from that loneliness eating life away, but just as easily, that decision might have failed. Still, martial arts seemed my best alternative at the time.

That night, the big country, became less about faith and more about action, taking the right action, and when in doubt of that action’s correctness, still taking action based on best-choices. Ultimately, our choices should produce more and better choices, dictating,

You must always come up screaming, even if you know you’re going to get knocked back down.

On October 24, 1997 my stepson hung himself from the deck at the back of our house.

Overcoming the Worst Anniversaries

He was 24.

I found him there, his lips purple, his body still as an empty shoe. He was hanging, a horror sculpture, motionless, silent.

I was pretty sure that his neck was broken, blue-black where the strap held him. I cut him down and he fell onto the grass below. I hurried down to his side.

His eyes were closed and his hands lay puffy — flat against his tan pants.

I tried CPR, but he was gone already.

From our home we have a glorious view to the east, and amazing sunrises. It’s the view that makes the place so special. You can’t visit our home without noticing the views, spectacular. But also this is where the deck is located, the deck from which our son hung himself.

There are many more details to our son’s death that day, too many: The way the metal buckle of the strap cut, bloodlessly, into his chin; the expression on his face, peaceful yet empty as a blank page; his last sounds, as I blew my breath into his body then heard that breath, a soft hissing slip back out.

There is my memory of his mother’s face, voice, and breath arriving home from work when the cops and firetruck, and ambulance were still blocking our driveway and when I told her what had happened.

There are memories of the way the sky looked that day, so peaceful and calm.

In December of that year, at Christmas, I gave my wife a bird feeder to hang from the deck in the place where our son had died.

The bird feeder had a green roof and Plexiglas sides. It held a couple of quarts of wild bird feed.

It hung from a piece of raw, brown rope. I wasn’t sure about hanging something from that spot — I wasn’t sure what to do and what not to do. Christmas that year was going to be pretty painful and awful no matter what, so I took a chance on the bird feeder.

The sunrises, of course, kept on coming:

In April the birds began to arrive, mostly sparrows and swallows, lots of others I can’t name. They landed and, chirped, dipped their beaks into the feed.

Quail cleaned up the spillage on the green grass where our son had fallen when I cut him down.

The birds, all that life, singing, soaring, heads turning quickly, gracefully from side to side looking for what?

All that life kept the feeder constantly in motion twisting slowly, even on the stillest of days.

Soon, somehow it was May. The birdhouse swarmed with life, flying, squawky, life-feeding life in a flutter of feathers, claws, beaks, and eyes.

The birdhouse was alive, in motion and somehow it started to help.

But in the end, as we approached the anniversary of our son’s death, we cut it down and put it away.

Because, in truth, nothing ever really helps, nothing but time and the slow and fast unfolding of life as more death, more loss, more heartbreak builds up and gathers, like birds around a feeder, like quail nibbling below it on the new spring grass.

The Death of a Friend

In 1990, my friend Phil called me wanting to talk, and wrapped in personal problems, I made an excuse not to see him. A few days later, he threaded a cinder block with a chain to weight his body and stepped from a bridge into a reservoir. Phil’s suicide rose out of a bad breakup with a girl who lied about being pregnant, but there were many other issues. His death crushed me with guilt for nearly a decade until finding some peace in that martial arts studio.

In 2001, Stuart Adamson, lead singer for Big Country, committed suicide after suffering issues compounded by addiction. Had Adamson died before that day in the martial arts studio, my cynicism would have deduced the meaninglessness of In a Big Country. Not long before that day, in my days of prayer, faith would have dictated Adamson lost God. By the time he died, I understood suicide as a great mystery since the dead cannot tell us their reasons. We like to think we have complete autonomy over our actions, but social pressures, experiences, disorders, and many other factors weigh heavily on choices. Did Adamson or my friend Phil even have a choice?

We don’t know.

Forgiving Hemingway

SOMETIMES HEALING OURSELVES IS HARDER THAN IT SOUNDS!

I’m trying to forgive Hemingway for his suicide. I know of at least one former friend who, reading this, would tell me “Hem doesn’t need your forgiveness!” and of course this old friend would be right. But this is not about what Hemingway needs, it’s about me. And about my not buying a shotgun and not deciding that my desire to escape my pain matters more than anything or anyone else. That’s what this poem is about and what life is all about on our journeys to knowing ourselves, healing ourselves, or ending ourselves (always an option). And it’s okay, Hem, that you either never knew or briefly forgot, maybe because you had a shitty day or maybe because you had a perfectly clear one, after all life can be pretty vicious. Either way, whether you need my forgiveness or not, you got it. I just hope I never need this kind of forgiveness. But we never know.

Stay Alive

Judging suicide’s decision-making is more imaginative than factual, making a “why” debate somewhat pointless, but perhaps more useless is distilling wisdom from that mysterious act. Entertaining ways the person could have avoided their fate conjures another “what ifs” debate of options that clearly held no possibility for the person at the time.

What we know is the wisdom apparent In a Big Country, here and now. Adamson and his bandmates poeticized hope, giving us an answer we can tap toes with beat, study, and apply to make choices. Here and now, in that place of choice, we grasp Big Country’s message sung so many years before,

I’m not expecting to grow flowers in a desert

But I can live and breathe and see the sun in wintertime

In a big country, dreams stay with you

Like a lover’s voice fires the mountainside

but only if you

Stay alive.

Copyright Vincent Triola & Terry Trueman

Personally I like the Spotify Version better.

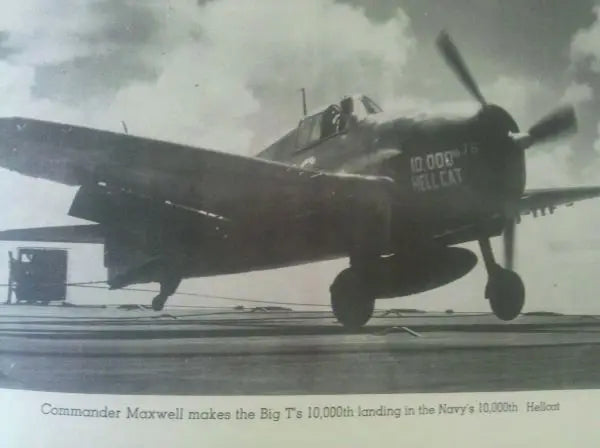

Pic of my dad’s WW2 aircraft (a Hellcat) landing on his WW2 Carrier (The Ticonderoga)

Photo by Gian Reichmuth on Unsplash