Rethinking Performance Pay

Working in a labor-intensive field, moving and storage, one of the most shocking things I learned was how little motivation is instilled by pay-for-performance. Higher wages and bonus incentives were simply not valued by most workers. As a manager, I grappled with this idea because, rationally, paying people more for more work should incentivize the tasks. I made excuses, like it was an individual worker issue or that the pool of workers was wrongly fitted to the job. I continued this practice even as I became an owner of a company, believing that having more authority would allow me to incentivize work in a more effective manner. This thinking was wrong, and the company I had ultimately failed due in large part to labor cost issues.

The repeated use of pay-for-performance failed no matter what form I used.

The reason pay-for-performance fails is both simple and complicated, making for a frustrating business practice. It often leads to adopting undesired methods such as micromanagement and negative reinforcement, which many managers resort to using out of a sense of futility.

What is Pay-For-Performance?

In today’s competitive business environment, organizations are constantly striving to find effective ways to motivate and incentivize their employees. This desire is not limited to large companies, but also extends to small business owners who often face even more time and labor-intensive projects.

Pay-for-performance, also known as performance-based pay, is perhaps the most popular approach that aims to reward employees based on their individual performance or the performance of the organization as a whole.

The concept of pay-for-performance is rooted in the idea that rewards, such as financial incentives, motivates employees to perform at their best. The logic is simple: if employees know their performance directly impacts their compensation, they will be more motivated to work harder and achieve better results. Proponents of pay-for-performance argue that these rewards provide a clear link between effort and reward, giving employees a sense of control over their earnings and motivating them to excel in their work. In theory, this seems like a win-win situation for both employers and employees.

Implementation of this strategy appeals, to many organizations due to its simplicity, but, as I learned, application reveals limitations – some extremely costly. The reasons why paying for performance often fails to deliver long-term results mires in reasons both simple and complex but understanding can help you avoid a lot of frustration and financial loss as well as provide profound lesson concerning personal and organizational development.

Problems with Bonus Pay and Incentives

Inconsistent Data

A primary issue with pay-for-performance is the lack of consistent data. In some instances, research shows performance pay works, while in others, it does not at all. Part of this inconsistency seems to be due to mitigating factors of performance pay’s routine use, temporal effects, types of incentives (extrinsic vs intrinsic), and likely many other individual traits.

Routine Use of Pay-for-Performance

Another problem is the reliance on bonus pay and incentives as the primary motivator. If monetary rewards are provided too routinely, such as a quarterly bonus, they become expectations rather than rewards.

Contrary to popular belief, bonuses don’t always motivate employees to perform at their best. In fact, they can sometimes have the opposite effect. One reason for this is the phenomenon known as the “crowding-out” effect. When employees are solely focused on earning a bonus, they may neglect other important aspects of their job, such as collaborating with colleagues or developing new skills. This narrow focus on the reward can hinder long-term growth and innovation within the organization.

Temporal Effects

Performance pay seems to provide no long-term motivation for employees. Surveying “compensation professionals” about merit and bonus pay systems the results showed that these incentives as "marginally successful". These results revealed a decrease in confidence for pay for performance by organizations, which a decade prior viewed pay for performance as “marginally successful”. This decline in opinion could be the result of many factors but clearly time has not shown performance pay to have improved worker motivation in the long run with organizations in general.

Research has shown that monetary rewards can be effective in motivating simple, routine tasks that require little creativity or cognitive effort. However, when it comes to complex tasks that require problem-solving and innovation, the impact of bonuses and incentives diminishes significantly.

Well, how do you explain the in my case and many others performance pay’s failure to motivate labor? If performance pay worked with simple tasks, there would not be labor shortages on the scale we see today. We can explain this phenomenon with time, such that any performance pay system will fail when implemented too long.

Coupled with the idea of routine, performance pay also, can simply lose effectiveness for other reasons, such as not being worth the effort. If a company offers a bonus in conjunction with payroll, in time, other factors (personal and organizational) will likely change and what once motivated employees is no longer valuable. For example, if hours needed to achieve the incentive increase, the bonus may not be worth the effort. Likewise, if a worker’s circumstance changes, such as marrying someone and ultimately increasing family income, they may be unincentivized to obtain the bonus. Such examples can work both ways but ultimately show the temporal vulnerability of pay-for-performance systems.

Understanding the Motivation behind Pay-for-Performance

Much conjecture explaining the success and failure to motivate revolves pay-for-performance. Many of the theories and assumptions have merit because they often describe situations that commonly occur, such as in my case, the failure to motivate laborers. Most explanations for pay-for-performance failure resides in either the form or implementation of reward.

Form of Incentive (Extrinsic vs Intrinsic)

Pay-for-performance systems fall into the category of extrinsic rewards, which refers to tangible benefits external to the actual work being performed. These rewards can take the form of bonuses, commissions, or other financial incentives.

As discussed, these extrinsic incentives often fail which led to the idea that other forms of motivation are superior: intrinsic rewards. Intrinsic rewards are personal in nature such as a sense of accomplishment or the motivation of having the boss say, “Good job.” These motivations vary tremendously due to their subjective nature and help explain the failure of pay-for-performance in the long term. Research reveals intrinsic motivation, which comes from within oneself, is a stronger driver of performance and job satisfaction compared to extrinsic motivation. When employees are intrinsically motivated, they are more likely to take ownership of their work, seek out challenges, and strive for personal growth. In contrast, excessive reliance on extrinsic rewards can undermine intrinsic motivation and lead to a decrease in overall job satisfaction.

Recognizing the limitations of pay-for-performance, organizations are exploring intrinsic rewards. This involves creating a work environment that fosters autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Theoretically, by providing employees with opportunities for personal and professional growth, organizations can tap into their intrinsic motivation and create a sustainable culture of high performance.

Readily, the problems appear in this thinking as not every company has the means to create personal and professional growth opportunities. Types of work also limit intrinsic motivation because creating a work environment that fosters autonomy, mastery, and purpose is not possible in every company, such as retail and labor industries which require following specific methodologies like preparing the workplace the same way each day or customer service that should be the same throughout the organization.

The more bureaucratic the organizational need, the less opportunities for the company to provide personal growth.

Limited Connection to Company

Another reason performance pay often fails is explained by the employee’s limited connection to company objectives and goals. Compensation plans focused solely on organizational performance and growth overlooks the individual employee. Theoretically, the individual employee’s goals and values must be aligned with the organization so aligning goals and objectives in this manner, the organization’s culture transforms and focuses on improvement.

Again, problems arise with attempting to align individual goals with organizational goals, most notably that it is not always possible. It would seem easy to align the goals of increased sales with an employees goals to better herself financially, educationally, etc., since these goals are likely dependent on the pay from the organization. Yet, this does not happen because in many instances neither employee nor organization can marry these goals because the goals are never truly aligned.

For an employee to "own" their job, they must feel a sense of indispensability or necessity because without this sense, the job cannot be meaningful. A doctor is necessary to the treatment of a patient. A lawyer is necessary to the defendant or the plaintiff to help adjudicate the case.

How can you have a deep connection to a company if you are not necessary or indispensable to the operation?

Worse than not being aligned with the company’s goals, employees are more likely to form resistance because of their vulnerable positions. If they believe their job is on the line or they have been unjustly treated, employees can become resistant and perform below average, having the opposite effect. Resistance can form this way when a company attempts to align individual with organizational goals and this support is seen as disingenuous. This can happen even in the most well-meaning of situations, such as when an organization attempts to provide support for personal goals but loses a large account and must cut programs or reduce hours. These situations can make companies appear hypocritical and thus reduce employee performance.

The Total Opposite Effect

Perhaps one of the worst pay-for-performance effects is the way they can lead to long-term organizational corruption. Cases such as WorldCom and ENRON show how pay-for-performance may yield short-term improvements in employee performance but also have unintended consequences, like bottom-line thinking. When employees are solely motivated by financial rewards, they may engage in bottom-line thinking that prizes profit above ethics. In cases such as ENRON and WorldCom the organizations became corrupt at all levels as profit become the only goal. These examples minimally reveal how pay-for-performance leads to employees cutting corners to achieve their targets, which can severely harm the company’s performance and reputation.

What are we missing?

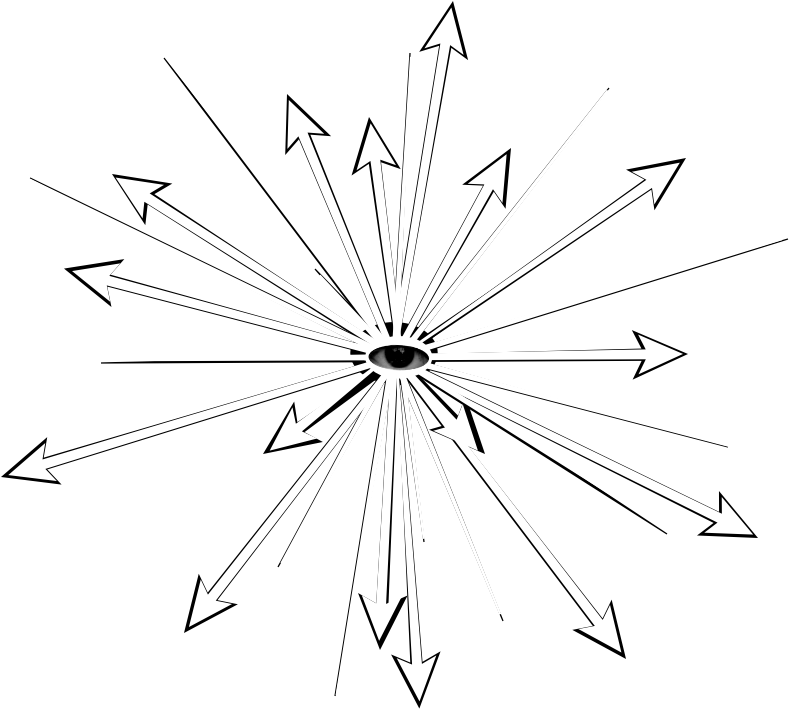

Pay-for-performance systems are far from reliable and often unpredictable. By looking at pay-for-performance flaws, the conflicting research, and experiences, we realize some component of motivation that goes beyond forms of rewards is missing. From experience and studying of performance pay, an individual factor of motivation elucidates as the unknown quantity.

Clearly, when we discuss motivation at the personal level, whether extrinsic or intrinsic, rewards vary tremendously in effect in accordance with the individual. Someone motivated by receiving a free vacation may not be motivated by a new car since tastes vary. The very nature of intrinsic rewards defines them as subjective meaning they would need to be personalized is some way, making the alignment of organizational goals with personal goals a tremendously difficult task, even for the best of companies. With all the flaws, unknowns, and risks of pay for performance, perhaps a more intensive examination of motivation at the personal level is warranted.

Original photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash